Originally written in 2015. Still hits like it was written today.

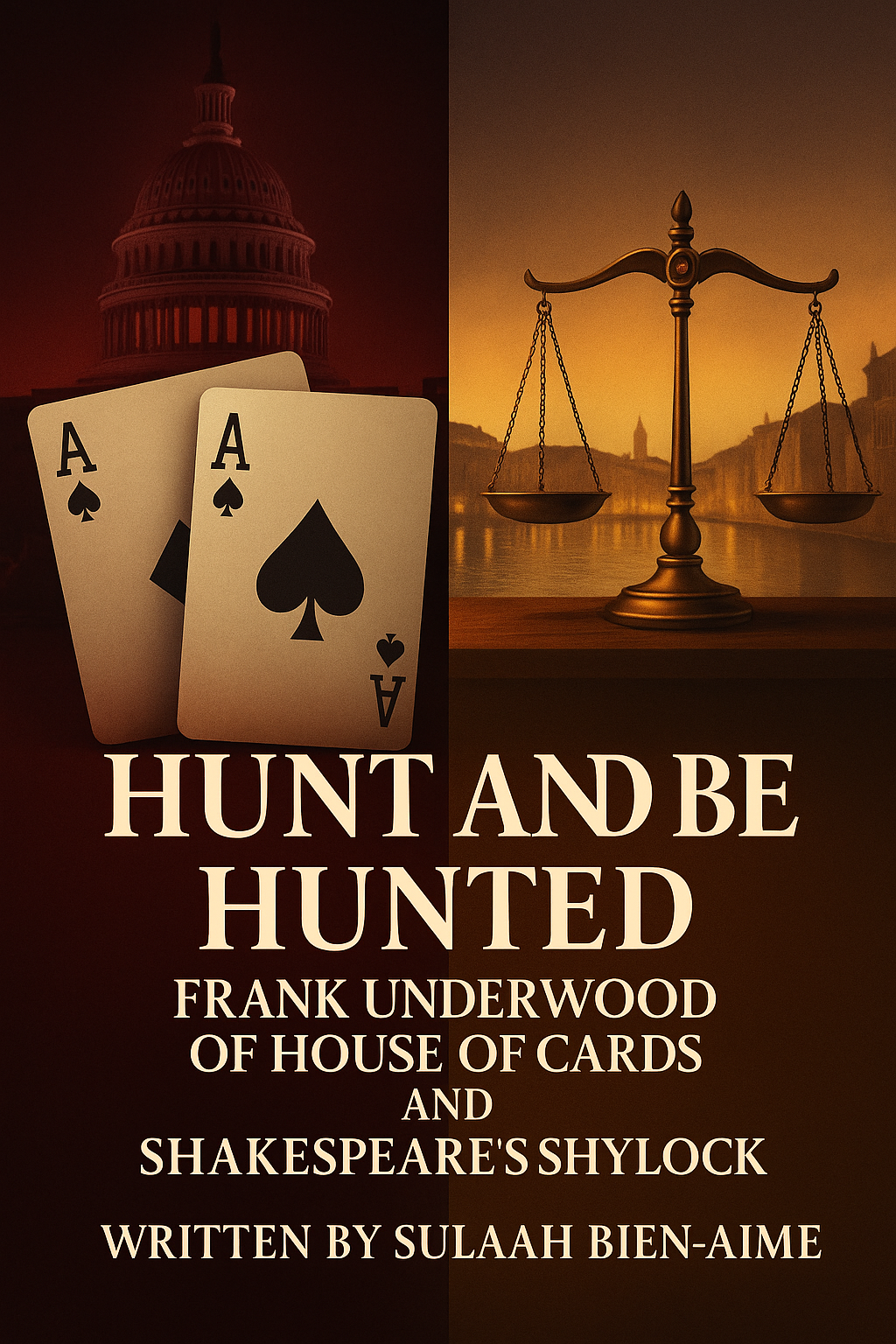

Hunt and Be Hunted: Frank Underwood of House of Cards and Shakespeare’s Shylock in The Merchant of Venice

By Sulaah Bien-Aime

Two recurring themes arise in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice that create a powerful duality in the character of Shylock: self-interest and mercy. Though Shylock is not the principal character, he stands out as the antagonist — the lone Jewish businessman tolerated for his money but shunned and ridiculed for his “ethnicity.”

We are introduced to a man seemingly devoid of mercy, stripped of humanity in the eyes of Venetian society. His calm, calculated resolve surfaces in his chilling monologue to Salarino:

“He hath disgraced me… scorned my nation… cooled my friends, heated mine enemies — and what’s his reason? I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes?… If you prick us, do we not bleed?… And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?” (Mahood 110)

This passage reveals Shylock’s internal conflict: the businessman vs. the man. He questions his rejection — asking if he, too, is not made of flesh and blood. Yet these questions aren’t posed for resolution. Shylock is not seeking mercy; he’s seeking vengeance. His wealth elevates his status just enough to give him leverage — and he uses that leverage to bite back at those who’ve abused him.

Shylock’s tone is even, firm, and quietly sinister. He is methodical. His request for Antonio’s pound of flesh isn’t desperation — it’s design. Antonio becomes a symbol of retribution — collateral in a society that denied Shylock humanity.

Even in disgust, Shylock remains transactional.

“To bait fish withal, if it will feed nothing, it will feed my revenge.”

His logic is brutal: no action comes without payment. Even condemnation is a currency. And while we sometimes see glimmers of his humanity, those moments are quickly eclipsed by his burning need for revenge.

The law plays a central role in The Merchant of Venice, and Shylock plays it like chess. He adheres to the rules, learns the system — and uses it against the very people who used it to oppress him. In a twisted way, he flips their world back on them. Antonio’s signature isn’t just a contract — it’s a trap, legally constructed, morally ambiguous, and wholly intentional.

Now shift to House of Cards — Netflix’s 2013 political thriller starring Frank Underwood, a Democrat from South Carolina passed over for Secretary of State. The series follows his ruthless climb to ultimate power.

Underwood’s world mirrors Shylock’s, though modern and political. When passed over, Frank doesn’t react — he plots. Every step is calculated. Every smile hides a knife. His philosophy is summed up in this bone-chilling monologue, delivered just after murdering the once-trusted journalist Zoe Barnes:

“Don’t waste a breath mourning Miss Barnes. Every kitten grows up to be a cat… For those of us climbing to the top of the food chain, there can be no mercy. There is but one rule: Hunt or be hunted.” (House of Cards, Season 2)

Frank and Shylock are guided by the same core belief: I’ve been wronged — and someone must pay.

For Shylock, it’s the Christians who mocked and belittled him.

For Frank, it’s the political system that overlooked his brilliance.

Shylock’s cruelty comes from being dehumanized. We feel a sliver of compassion for him. He might have been a different man if accepted as an equal. But with Frank? We sense he thrives on being disliked. He revels in being feared. It’s part of his power.

The murder of Zoe Barnes isn’t just a plot twist — it’s Frank’s initiation. The moment he goes full predator. From there, everything is fair game. His schemes are flawless. His hands rarely dirty — just like Shylock’s. Both of them manipulate others into weakness. Both use power systems — religion, law, politics — as weapons.

Yet there’s a difference.

Shylock has a child.

Underwood does not.

And that distinction matters. Shylock, despite everything, has some emotional tether to the world. He is capable — barely — of compassion. We see it when his daughter betrays him by selling a ring from his dead wife. The hurt is real. He’s not a cold-blooded killer. His hands are clean — even when his heart is not.

Underwood, on the other hand, has no such tether.

No child.

No emotional weight.

His detachment makes him feel less human. His love for power is all-consuming — it’s his wife, child, and god rolled into one. Even his relationship with Claire feels sterile, transactional — two loners playing house with power as their shared addiction.

Shylock and Underwood are both architects of their own narratives. They bend rules, exploit systems, and seek revenge. But their motivation separates them.

Shylock’s rage is rooted in being rejected.

Underwood’s rage is rooted in being overlooked.

One is trying to reclaim dignity.

The other is trying to dominate it.

Both are dangerous.

But only one, perhaps, is still searching for what it means to be human.

+There are no comments

Add yours